Quantum you can hold: The rise and the promise of superconducting qubits

By Katia Moskvitch and Tom Dvir

As the year 2025 – what UNESCO has declared the International Year of Quantum – draws to a close, the anticipation of what awaits us in quantum next year is kicking into higher and higher gear. So much has happened just in the last few months in this still relatively young field that even those who hadn’t heard of quantum computing a few years back are now paying close attention. “To make progress, we need problems to be solved at every layer of the stack, right from the bottom where we have the qubits, to the classical control and so on, and all the way to the algorithms,” says Itamar Sivan, the CEO of Quantum Machines. “We need breakthroughs everywhere.”

And while some qubit modalities may be enjoying more limelight than others, there have been significant developments right across the qubit playing field. As for superconducting qubits, the awareness has gone through the roof thanks to this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics. The award recognized one of the biggest breakthroughs in quantum – the work of three researchers who back in 1985 paved the way to today’s superconducting qubits, tiny circuits you can see with your bare eye.

John Martinis, Michel Devoret, and John Clarke’s work has propelled physics forward and redefined what we thought was possible. In their experiment, described in a Nature paper, they showed that tiny circuits made of billions of electrons, a beautiful example of our daily macroscopic world – obeyed the rules of quantum mechanics. Prior to that, those rules were reserved for the realm of atoms and subatomic particles, definitely not something you could hold in your hand.

Specifically, the trio studied superconducting electrical circuits exhibiting quantum behavior, governed not by individual electrons but by a collective macroscopic variable: the quantum phase of the superconducting condensate formed by many Cooper pairs acting together, a concept rooted in earlier theoretical work on macroscopic quantum systems.

Typically, negatively charged electrons repel each other, but inside certain materials at very low temperatures, an electron can distort the material’s atomic lattice. This distortion then attracts another electron, making the two particles loosely linked. In a superconductor, huge numbers of these Cooper pairs condense into a single quantum state.

Martinis, Devoret and Clarke decided to see whether a macroscopic degree of freedom such as the collective phase or current of many Cooper pairs in a superconducting circuit could itself behave quantum mechanically.

Their experiments involved the Josephson junction, a tiny superconductor–insulator–superconductor ‘sandwich’ in which electrical current can tunnel through an insulating barrier. In this system, they observed for the first time ever macroscopic quantum tunneling, when the collective superconducting phase, representing the motion of a huge number of Cooper pairs, tunnels between distinct quantum states. This was the first major hint that quantum mechanics can govern macroscopic degrees of freedom, not just microscopic particles.

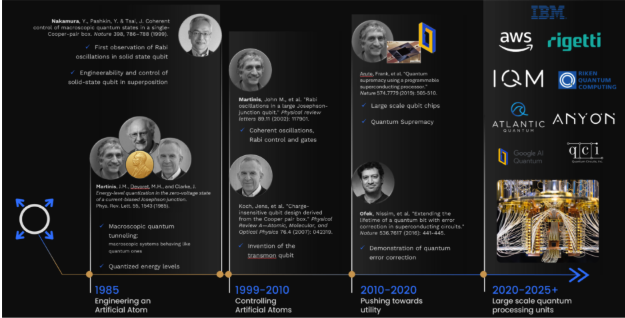

A timeline of milestones for the quantum processing unit. From a single spark in 1985, to an entire ecosystem

Artificial atoms and the birth of superconducting qubits

Then came an even more striking discovery. The researchers found that the energy stored in these circuits is quantized, forming discrete levels analogous to the orbitals of an atom. They created an artificial atom. Before these results, many experts doubted that quantum coherence could survive in devices made from macroscopic components. The environment was expected to destroy quantum information almost instantly. But the experiments by Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis proved otherwise. They showed that with careful engineering and low-temperature operation, circuits could maintain quantum coherence long enough for precise measurements, and eventually also quantum logic. The methods the three scientists developed for measurement, readout, device fabrication, and noise control are still at the heart of today’s quantum processors.

Key results from the 1985 work that ultimately led to the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics for Martinis, Devoret, and Clarke

There is another milestone that nicely complements their work – the breakthrough by Y. Nakamura and colleagues, who in 1999 demonstrated coherent control of a charge qubit. It was the first clear observation of Rabi oscillations in a solid-state qubit, and the experiment provided one of the earliest direct proofs that engineered superconducting circuits could be prepared and manipulated in genuine quantum superpositions.

In the years that followed, further advances bridged the gap between single-qubit physics and scalable quantum computation, most notably the development of circuit quantum electrodynamics, which enabled strong coupling between superconducting qubits and microwave resonators for high-fidelity control and readout. Those developments helped accelerate global interest in superconducting qubits and paved the way for many milestones that followed – including Martinis’s work in early 2000s, when he and his colleagues showed coherent oscillations, Rabi control, and quantum gates in superconducting qubits.

Devoret’s work at Yale also led to major advances in measurement theory and to improved qubit designs, ultimately culminating in the landmark invention of the transmon qubit, now the backbone of most superconducting quantum processors. Meanwhile, Clarke’s pioneering techniques in SQUID design, ultra-sensitive readout, and noise spectroscopy enabled the precision measurements needed to push quantum coherence to new heights. Together with the first demonstrations of two-qubit gates and entanglement in superconducting circuits in the mid-to-late 2000s, these advances firmly established superconducting qubits as an important platform for quantum computing.

From laboratory breakthroughs to scalable quantum machines

By the 2010s, teams at Google, IBM, Yale, MIT, ETH and numerous other labs in industry and academia have started building directly on this foundation. That was the period when labs started to move from pure exploratory demonstrations to systematic engineering of superconducting quantum processors, increasingly focusing on reproducibility, fabrication yield, and control at scale.

Fast forward to the twilight of 2025 – the superconducting quantum computing playing field boasts multi-qubit architectures, much longer coherence times than ever before, higher-fidelity gates, and increasing progress in error mitigation and error correction. Ever larger superconducting systems are being deployed, such as the 256-qubit machine by Fujitsu and RIKEN, a major step toward more complex algorithms. Worth noting also IBM’s hardware successes, including the launch of its 120-qubit Nighthawk processor with a new square-lattice architecture designed to support deeper circuits with thousands of gates.

Roadmaps from industry and academia outlining specific paths toward larger, fault-tolerant superconducting systems increasingly emphasize logical qubits, and there are companies like Qolab that are working hard on creating more stable, better qubits from the get-go. This startup, co-founded by John Martinis, has recently deployed one of its superconducting qubit devices at the Israeli Quantum Computing Center (IQCC), a very promising collaboration on the path towards quantum advantage.

But it’s not just about qubit hardware. This year has also seen significant progress on the control side, with a growing number of experimental demonstrations relying on programmable, real-time classical control to push performance further. One prominent example is recent work published in Nature on fluxonium qubits, where real-time feedback and fast control were essential to stabilizing operation at optimal working points and achieving high coherence and gate performance (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09687-4). Similar advances reported in leading journals across superconducting and hybrid quantum systems increasingly depend on low-latency pulse sequencing, fast feedback, and real-time calibration – capabilities provided in several of these experiments by Quantum Machines’ OPX control platform.

These results show how programmable, real-time classical control is a key enabler of high-fidelity operations, longer effective coherence, and scalable quantum architectures. As the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology draws global attention to the field, the focus has clearly shifted from simply building qubits to making them truly useful. That’s progress – and we should celebrate these achievements as well as celebrating this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics and human ingenuity.

Our ability to design, control, and compute with quantum states in human-made devices is remarkable, and it will only get better, bringing our fault-tolerant quantum tomorrow more and more within reach.