Scaling spin qubits with hybrid architectures: remote coupling via superconducting circuits

Spin qubits offer a compelling path toward large-scale quantum computing.

However, the length scale over which spin qubits naturally couple to one another is very short, of order just a few tens of nanometers – and that poses a key challenge for scalable architectures. In our latest work, we demonstrate a new approach, where we couple remote quantum dot spin qubits using a superconducting qubit as a tunable mediator. The approach opens a promising route to scalable spin-based architectures that use long-distance coupling to integrate dense spin qubit arrays with classical control electronics on chip.

What are quantum dot spin qubits? They are a type of quantum bit where quantum information is encoded in the spin of an electron that is confined inside a semiconductor quantum dot. Gate-defined quantum dot spin qubits have been attracting significant interest as they combine two critical advantages for scaling: compatibility with standard CMOS fabrication and a small physical footprint, of the order of nanometers. Together, these properties help to envision systems with millions of qubits integrated on a single chip. However, this same density creates a central architectural challenge. As systems grow, routing classical control and readout signals becomes increasingly complex, threatening to undermine scalability.

One proposed architecture for spin qubits addresses this challenge by organizing qubits into tightly coupled local blocks, or “pockets,” while embedding classical electronics directly on the quantum chip. To make such architectures viable, we need long-range coupling mechanisms that can connect spatially separated spin-qubit regions without introducing excessive wiring overhead or noise.

Spin qubits, however, naturally couple only over very short distances. Their native interaction, the exchange interaction, operates over tens of nanometers, far shorter than the distances required to connect remote blocks. The key question, then, is how to introduce robust, controllable long-range coupling between spin qubits.

Why use a superconducting qubit as a coupler?

Researchers are working on several approaches to long-range spin coupling. One well-studied route uses superconducting resonators to mediate interactions between spin qubits via photons. While promising, this method has a fundamental tradeoff: strong coupling requires high-impedance resonators, which tend to be lossy and limit achievable gate fidelity.

We take a different approach, inspired by techniques routinely used in the superconducting qubit community. Instead of a resonator, we use a superconducting qubit as the coupling element. Superconducting qubit couplers already play a central role in connecting superconducting data qubits, and we ask whether the same concept can extend to spin qubits, potentially avoiding the losses associated with high-impedance resonators.

Superconducting qubits can be understood as nonlinear LC oscillators, where a Josephson junction introduces anharmonicity that allows selective control of two energy levels. These qubits support fast operations and readout, albeit with a larger physical footprint than spin qubits. Crucially for hybridization, superconducting qubits have the potential to act as highly controllable, fast mediators.

On the spin side, our work focuses on exchange-only qubits implemented in silicon/silicon–germanium quantum dots. Local gate electrodes confine electrons, while barrier gates tune their interactions. Exchange-only qubits offer a key advantage for hybrid systems: they operate without requiring external magnetic fields, which are problematic for superconducting circuits. Qubit states are encoded within a triple quantum dot, and can be controlled using locally applied electric fields.

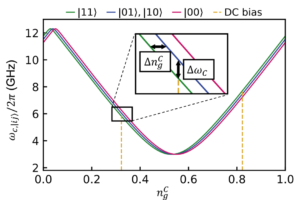

The coupling scheme we implement relies on an offset charge-sensitive transmon (OCS transmon). This device closely resembles a standard transmon, but with reduced capacitance, making its energy levels more sensitive to charge. In simple terms, smaller capacitor plates make the addition of a single electron more impactful, allowing the transmon frequency to respond more strongly to nearby charge configurations.

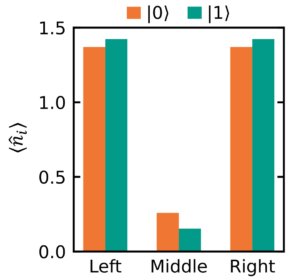

We operate the spin qubits in two distinct regimes. During single-qubit operations, the system remains in a decoherence-free subspace, where the three quantum dots sit at equal potential, suppressing noise. To activate coupling, we shift into a resonant exchange regime by raising the potential of the central dot. This redistribution of electron occupancy creates a state-dependent charge configuration of the quantum dots, and therefore a state-dependent electric dipole.

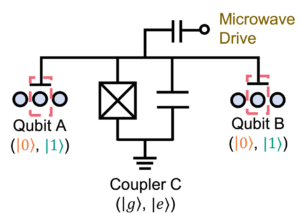

When two such resonant-exchange qubits couple capacitively to the OCS transmon, as shown in Figures 1 a, b and c below, their state-dependent electric dipoles induce state-dependent shifts in the transmon frequency. By driving the coupler conditionally, we generate a controlled phase interaction between the remote spin qubits. This geometric phase gate follows principles familiar from other qubit platforms, but here it operates on superconducting-qubit timescales, enabling fast gates.

Fig. 1a. Circuit diagram depicting the coupling of two quantum dot qubits via a superconducting qubit coupler

Fig. 1b. Electron occupancies of the three quantum dots making up the resonant exchange qubit, depending on the qubit state

Fig. 1c. Resonance frequency of the superconducting qubit, ω_C, for all four possible two-qubit states of the quantum dots, as a function of coupler gate charge

We analyze multiple gate implementations, including fast off-resonant gates and slower sequences incorporating dynamical decoupling to mitigate low-frequency noise. Which approach proves optimal depends on the exact device’s noise spectrum and requires experimental validation. Importantly, theoretical modeling indicates that gate fidelities far exceeding 90% are achievable with realistic parameters.

Building a hybrid qubit infrastructure

Executing this hybrid coupling approach requires a measurement infrastructure capable of operating superconducting and spin qubits simultaneously. We’ve designed a hybrid setup that integrates both modalities within a single dilution refrigerator, drawing on best engineering practices from the superconducting qubit community. The system supports DC and baseband control for quantum dots, alongside microwave control and readout for superconducting qubits in the 2–10 GHz range. Custom PCB designs manage signal routing, filtering, attenuation, and recombination while minimizing crosstalk and spurious modes.

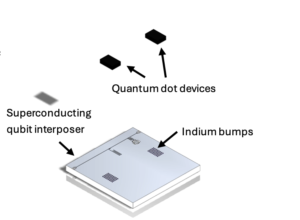

A key step toward full integration is 3D assembly via flip-chip bonding, as shown in the schematic of Figure 2. This method allows independent fabrication of the quantum dot device and the superconducting interposer, followed by bonding with indium bumps. Initial validation tests of our flip chip process using dummy devices, which confirms reliable DC connectivity down to millikelvin temperatures.

Fig. 2. Schematic showing the flip chip bonding of two quantum dot devices to a superconducting qubit interposer chip

Before attempting coupled experiments, it’s important to verify that our hybrid measurement infrastructure supports high-fidelity operation of each modality independently. Superconducting qubits exhibited stable T₁ and T₂ times, exceeding 100 us, over extended measurements, along with qubit temperatures of around 40 mK, consistent with expected qubit temperature at the base temperature of the dilution fridge. On the quantum dot side, initial charge stability measurements confirm robust DC operation, with ongoing work focused on Pauli spin blockade and full qubit characterization.

As our next step, we will integrate quantum dot devices with the superconducting interposer and perform long-range coupling experiments. Beyond enabling scalable spin-qubit architectures, this work also points to a broader opportunity: hybrid systems that combine the fast operation of superconducting qubits with the long lifetimes of spin qubits. Determining how best to exploit these complementary strengths remains an open and exciting direction of future research.

For more information on this work, please see H.Kang et. al., Phys. Rev. Applied 23, 044055 (2025)